Let me introduce you to the scientific community with an example from last year. Upon being alerted to a man spending several days living as a goat, how do you think they responded? Did they treat this individual with scorn? Nope. Did they mock him mercilessly and make goat impressions every time he walked into the office? Wrong again. Did they award his contribution to science and sing his praises for doing so? Yes, how did you guess? Welcome to the weird and wonderful world of the Ig Nobel Awards, whose [apt] philosophy is to recognise studies in science, arts and everything in between which “makes you laugh and then think”. Interestingly, another Ig Nobel Award winner from last year won for [also] creating prosthetics and living as a badger, an otter, a fox, and a bird. I never said scientists were a normal bunch, now did I.

If you are not already aware of this fantastic award I would strongly recommend you browse the past winners. I could go on all day about the weird and wacky studies which scientists felt were important to carry out but, beyond goat-man, I recommend reading about the Physiology and Entomology prize winner in 2015. His dedication to his study is nothing short of breath-taking (you’ll get the puns when you read it, honest.)

Now, as many of you may be aware, with varying levels of hatred, statistics are a thing. They may pose a substantial headache for students and researchers alike but their correct use is important. Although far from fool-proof, the use of statistics allows us to pose and answer scientific questions and address hypotheses where the effects are incredibly subtle. Notice I say ‘correct’ use of statistics. There is little stopping people using statistics with little appreciation of their meaning.

One big issue is the over-zealous use of correlations. Now, correlation and causation are mixed up constantly and a lot of faith is placed in associations. The example I tend to use with students is the evidence that babies are in fact brought by the stork. We see a correlation between storks nesting outside a hospital and the number of babies born at that hospital. This effect is seen across Europe. Clearly, this suggests that storks are responsible for infants (unsure why they need to make their exchange at hospitals but there you go). This is, of course, ridiculous. There is likely some confounding variable which can explain why there is a large correlation between these variables. However, unquestioned acceptance of correlations here would lead us to some bizarre conclusions and irate women. If you want to find other amusing correlations, then you can procrastinate with this website. It should hopefully make this point clear in a hilarious way. Now, poor statistics and the Ig Nobel award came together in a beautiful way in 2011. It’s time to consider a dead salmon, an Ig Nobel award, and a method for bringing your dinner plans back to life.

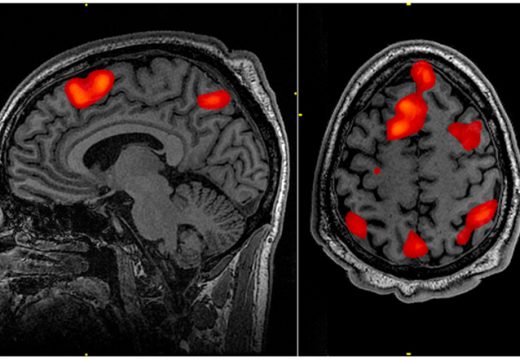

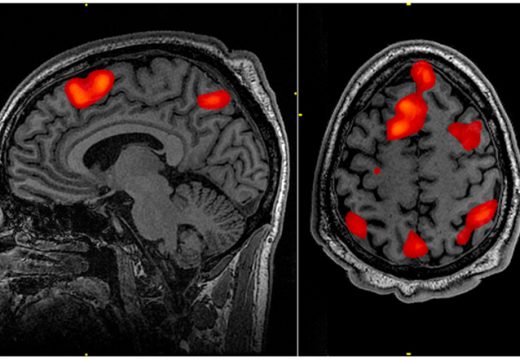

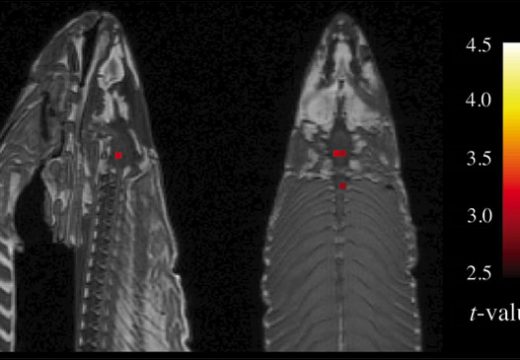

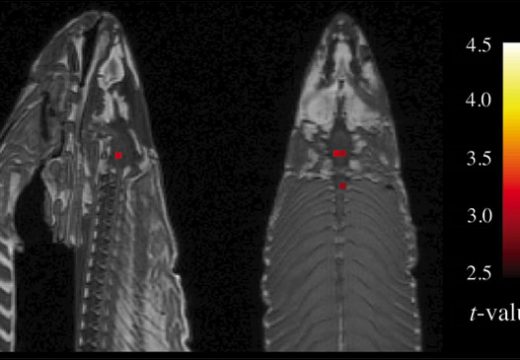

A group of researchers, led by Dr Craig Bennett from the University of California, were carrying out a study on emotion in social settings using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). fMRI is a technique commonly used in psychology and neuroscience to enable researchers to peer into the skull of an individual and, through the use of complex statistical analysis, to understand which areas of the brain are most active by assessing blood flow. The use of blood flow is a necessarily indirect way to assess the energy consumption of brain cells in specific regions.

The researchers decided to pilot their experiment in the scanner and they chose to use a dead salmon for this purpose (which was apparently delicious in the end). They then proceeded to ask the salmon to respond to social situations with an appropriate emotion to make sure the pilot was appropriate, and hilarious, and then left the data for some time. However, when they came back to analyse the data, they found something bizarre. The salmon showed brain activity. Had the scientists worked out how to bring a fish back from the dead? Not quite, rather it was to do with the haphazard use of statistics (something which the researchers were well aware of).

Typically, when you carry out statistical tests you are mindful of how many you are performing. This is because, depending on the standard you set, there is always the possibility that you may find an effect simply due to chance (at least 5% of the time). The greater the number of statistical tests you carry out, the more likely it is that you’ll find an effect by chance (e.g. a false positive). This is a big problem across psychology and biomedical studies and linked to the replication crisis in these fields.

With this in mind, fMRI studies, like the salmon one described, involve thousands of statistical tests to assess what area of the brain is active during a given task. As a result, it is much more likely that an ‘effect’ is found purely by chance alone. This is what produced the seeming revival of the salmon. This research highlighted that studies should control for the large number of statistical tests their analysis necessitated. This ‘control’ can be carried out by setting the bar higher for when we say there’s an effect (e.g. make it harder for us to say that there is an effect when running our statistical tests). Some argue that this means we miss very subtle effects, but it does reduce the chance that false positives are found too – such as claiming a dead salmon has brain activity. These findings sparked considerable debate and forced researchers to re-evaluate their own practices, as any good scientists should when presented with evidence such as this.

Overall, silly research can help us further understand the world around us, even if the applications are not immediately obvious. The Ig Nobel awards recognise this and promote research that is quite frankly wacky and seemingly a bizarre waste of time. As you should now know, the strange things in science tend to be the more interesting as they usually force us to reconsider what we consider normal or appropriate. The salmon in a scanner reinforces problems in using statistics without thinking and should impress on you why statistics are important in the first place. As for the study where the man lived as a goat for several days, I’ll have to get back to you about the importance of that one…